| History of Columbiana County, Ohio - Harold B. Barth Historical Publishing Company 1926 ************************** HISTORY OF COLUMBIANA COUNTY CHAPTER XI EAST LIVERPOOL, CONTINUED |

Water Works - Authorized by an act of the Ohio Legislature in 1879 the East Liverpool Water Works was established shortly thereafter. A pump house was erected on the Ohio River shore just above Babb's Island and a large reservoir 350 feet above on Thompson's Hill, built with a capacity of 1,500,000 gallons.

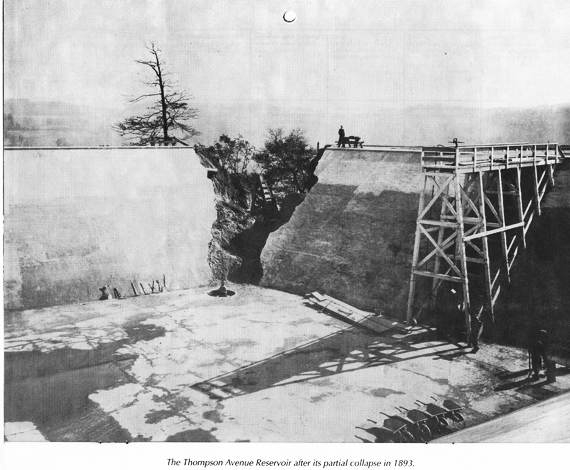

In 1894 a second reservoir on Huston's Hill, 300 feet higher, was erected and a second pumping station was set up midway between them. Then followed the building of a third reservoir in connection with that of No. 1 on Thompson Hill, with a combined capacity of 7,500,000 gallons. The value of the plant in 1905 was $240,000 with a then $140,000 indebtedness. The first Board of Trustees consisted of Josiah Thompson, Isaac W. Knowles and Thomas Arbuckle, with Christian Metsch as clerk.

Sometimes reservoirs had problems.

In 1915 a mechanical filtration plant was completed near the Pennsylvania State line at a cost of $565,000. It included a water tower on the hill west of Riverview Cemetery. As a result the two initially used pumping stations were dismanteled. By 1926 there were in use more than 40 miles of water pipes with a daily capacity of 7,000,000 gallons.

Agitation for the departure became active during the administration of Mayor Samuel Crawford when efforts were made to sink wells on Babb's Island and other plans considered. Following an inspection of the mechanical filtration plants in Pittsburg and vicinity by the "Committee of Sixteen" appointed by Mayor R. J. Marshall. In 1912 the plan as at present carried out what was recommended as the most feasible for the city. The City Council then took the necessary steps for proceeding with the project.

The first attempt for a universal water supply was the building in 1850 by Josiah Thompson of a reservoir on the east side of Walnut Street a basin of stones 40 by 100 feet and six feet deep which was fed by a strong spring near by. Many of the nearby families frequented the place for their daily supply of water.

Another spring was to be found on the top layer of clay that was to be found near the D. E. McNicol Pottery. It was so strong that the plant in that period used it for its water supply.

Though the reservoir finally had some homes connected to it with pipes it was in time discontinued by them and turned into a tank for the soaking of hoop poles.

In the early days the city depended almost altogether on wells for its water supply. The older inhabitants remember the chief ones which included that one in the middle of Market Street south of the Pennsylvania Railroad and just off the Market Street wharf; another was on the west end of Williams Cask Factory and was probably used to supply the initial pottery of the city which was built by James Bennett and operated by him and his brothers.

The Brawdy well about 60 feet back of the southwest corner of Union and Second streets, which was the property of the senior Dr. Ogden, was one of the pioneer watering places as was the Shenkel well on the southwest section of Third and Walnut streets. In later years an epidemic of illness was laid to it and it was condemned and filled.

Two springs that were once greatly in use were the Thompson Spring along the railway tracks off the Thompson Pottery and another in a stone house in Thompson Place.

The Willets well on Pennsylvania Avenue on the spot now probably occupied by the Okey Heddleston Grocery Store was of great value to the early residents of the city.

On south Walnut Street near the home of A. J. Scott, architect, was the Wirth well. On East Sixth Street was the Isaac Knowles well near the old end of the Knowles, Taylor and Knowles Pottery. Across the street from this well was a basin 20 feet in diameter that was fed from a spring which largely contributed to the needs of the plant of the D. E. McNicol Pottery.

Just north of Horn Switch was the Mrs. Parriran well on the present Smith Hardware Company site; farther to the west was the John Hardwick well just a few feet north of the Faulk Mill, midway between Green Lane and Dresden Avenue, on the plot that is now used as a freight yard. It was first owned by James McPherson.

The John Baum well was situated on the present site of the Crockery City Products Company. Still another was the Wassignaria well on West Fifth Street just off of Persimmon Alley near the home of the late Cornelius Cronin. It was 125 feet deep. Even now a portion of the wall surrounding the home is perhaps slightly sunken because of the presence near it of this one time deep pit.

Until it was closed more than a decade ago the Diamond well in the Diamond slaked the thirst of thousands from the several openings through which the sulphur water it supplied was exuded. It gave way to the need for more space for traffic in the Diamond and because a new water system had been arranged for the city, obviating its necessity.

For almost similar reasons the Monroe Patterson well, an artesian one, which he had dug in the rear of his home on West Fifth Street and which was reached through an alley was discontinued. For years previous to that, however, it furnished a water supply to hundreds of persons daily.

The Following Text is from The City of Hills and Kilns.

By 1820, residents could purchase or trade for all the goods and services they required, if not in East Liverpool, then at other locations in the area such as Pittsburgh and Steubenville. On 10 February 1830, John Babb purchased five pounds of coffee for one dollar and tobacco and shaving soap amounting to twenty-five cents from Daniel Culbertson.144 Gardening, daily food shopping and preparation, and retrieving water from wells or the river filled the days of most housewives.

While the use of natural gas for fuel and of electricity for heating and lighting was beneficial to most people and was viewed as a symbol of progress, they also contributed to an increased number of fires in the community. For example, on 11 January 1878 John Thomas noted in his diary that Dr. Thompson's house was "blown up" by natural gas. Fire protection in East Liverpool, as in most other nineteenth century communities, developed as a reaction to an increase in fires as the town grew in size, population, and real property. Potteries were especially susceptible to damage or destruction from fires. In March 1876 heat from a kiln set fire to the roof of the new "Dresden" pottery and the Tribune reported that only a driving rain storm kept it from spreading. The editor chided city officials for the lack of adequate fire protection. He stated, "For the protection and safety of our manufactories let us have some feasible means of defending ourselves from the clutches of a gigantic conflagration. Where is the talked of reservoir? Where is the hook and ladder company? Where is the fire engine?" There were continued cries for a fire company in later issues; with new multi-story factories, business establishments and dwellings being built throughout the town more than just a "bucket brigade" was needed. With the editor helping to raise the consciousness of the people, a hook and ladder company was organized in 1877 with about fifty volunteers and Robert Hague as captain. In July 1878 council purchased a hook and ladder wagon from the Caswell Improved Coupling Company.19 The volunteer firemen soon formed an organization and called themselves the Crockery City Fire Department.

Once a water works was established in 1879, the city and individual pottery firms put in fire hydrants. . .

One of the most important elements of effective fire prevention was the availability of an ample water supply to combat the flames. East Liverpool was very progressive in comparison with other Ohio communities in the establishment of a municipal water works. Although by the 1850s several large Ohio cities such as Cincinnati and Cleveland maintained reservoirs and piping systems, many towns did not construct public water systems until much later. A supply of water was needed, of course, for cooking, cleaning, and bathing in addition to fighting fires. In East Liverpool another need for a constant supply of water was created with the development and expansion of the pottery industry. With water an important ingredient in the manufacturing process, many potteries were subjected to great inconvenience and expense when they were unable to procure a sufficient supply during the summer season. Prior to the establishment of the municipal water works, the potteries, like the general population, relied on a supply of water from either the Ohio River or wells.24

Despite inconveniences to residents and potters alike, it was the 1874 fire that destroyed W.S. George's cask factory and nearly spread to several potteries that inspired editors of local newspapers to urge council to construct a water works and to sell public bonds in order to achieve the goal. The establishment of a water system in East Liverpool, however, was not without its share of delay and controversy. The initial action taken by officials was in September 1878 when council passed a resolution calling for a special election to vote on the erection of a water works not to exceed thirty thousand dollars. The voters approved this measure by a majority of 450 to 115 votes. A committee composed of Mayor M.H. Foutts, Christian Metsch, and H.R. Hill visited the water works in Birmingham and Butler, Pennsylvania in order to determine the best method at the allotted cost. They decided that a reservoir with a pumping station was the most practical method, considering the topography of the town. By June 1879 all of the necessary ordinances were in effect, bonds were issued and sold, trustees of the water works were appointed, specifications and surveys were completed, and bids for construction were solicited.

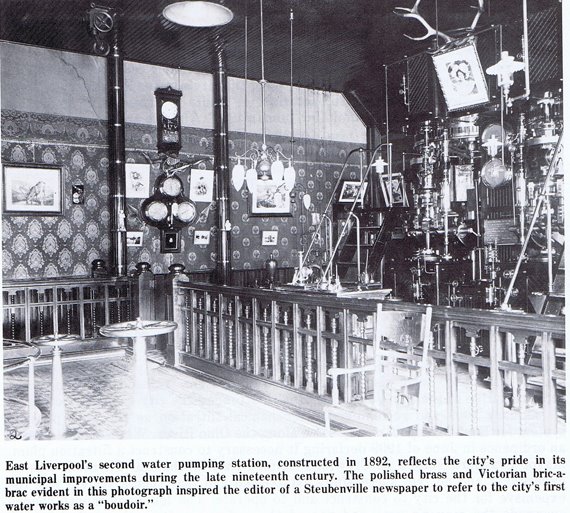

During the summer, the construction of the pumping station on the Ohio River and the million gallon reservoir which was 320 feet above the river on Thompsons Hill, in addition to the laying of pipe, began in earnest. Rates for residential, commercial, and manufacturing customers were established. A dwelling of one to five rooms would pay five dollars per year with an additional charge for private water closets. Saloons were required to pay ten to fifteen dollars a year for the privilege of running water, barber shops paid by the chair, and pottery manufacturers were charged twenty dollars for each thousand gallons consumed. When water was pumped into the reservoir for the first time in November 1879, it did not hold and emergency repairs had to be made. On 5 November 1879 water was released into the main pipes from the reservoir with appropriate ceremony, and the newspaper reported that all the plumbers in the city were busy connecting private customers to the main trunk lines. The editor of the Steubenville Herald visited East Liverpool's water works in 1886 and referred to the pumping station as unique. He continued: "The engine room presents more the appearance of a ladies boudoir . . . the floors being covered, walls papered and decorated with pictures and bric-a-brac, curtains and lambrequins at the windows, while fancy tables and easy chairs stood around. The engine stood in the center of the room ... [and] the large amount of brass ornamentation about the engine was polished in the highest degree."

The citizens of East Liverpool were obviously very proud of their new water works system. People were, of course, happy to get water to their homes for the first time, but at least one citizen complained of the additional cost to repair the reservoir. He also charged that public monies were used inefficiently when trustees went to Cincinnati to purchase a pump when it could have been ordered through the mail. Nevertheless, by the end of 1879 the central city had running water. But as the city expanded and population increased, outlying areas also needed to be supplied and the supply to the downtown area quickly became inadequate.26

City council received a petition from the residents of the Ohio City area in April 1886 requesting the extension of the city water mains into the east end. Following two months of deliberation, the water works trustees reported that the water line could not be extended to the east end at that time because of a lack of money but that it might be feasible the following year. The question of extending the water mains arose again in the spring of 1887. At this time it was known that Knowles, Taylor and Anderson were preparing to construct their large brick and sewer pipe factory in the east end and the editor of the Review took a stand favoring extension of the water system. He noted that with the extensive new enterprises in progress and those being contemplated, the east end was destined to be a populous section of the city. Council instructed water works superintendent Philip Morley to investigate the matter. Morley reported in May that the extension of the system would cost $8,461.78, not including fire plugs. Unable to procrastinate any longer, council agreed to hold an election to determine if the voters wanted the line extended and if they would approve the issuing of bonds. The question was overwhelmingly approved by voters although a mere 214 citizens bothered to cast their ballots. City council issued the bonds and construction began. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s citizens continued to support bond issues for the water department. Water pipes were extended into various sections of the city and additional reservoirs were added until by the turn of the century over twenty-five miles of water pipe serviced the community.27

One of the major reasons for increasing the capacity of the water system in East Liverpool, other than the growth of the population and the addition of new neighborhoods and potteries, was the installation of a sewer system. The editor of the Tribune began calling for the installation of a sewage system in 1883. He stated that the city had borrowed money for schools and the water works, why not do the same for the much-needed system of sewers? "In some places," he added, "the stench is almost unbearable." In August 1884 council voted to provide a system of sewage and drainage and ordered the city solicitor to draft an ordinance creating a Board of Sewerage Commissioners. During the months that followed, engineering surveys were made, but it was not until 1889 that the downtown area (District 1) was serviced by sewers. Since connection to the sewer lines was not compulsory, only 189 "hook-ups" were made. The rest of the city was not serviced untillater.28

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law

though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.