This is a complex topic covering approximately 40 years and several companies. Far too complex and to cover in any real depth there. What we will attempt to do here is a give a bit of a overview of this topic as it applies to the immediate East Liverpool area. For those who are interested in a more complete coverage we highly recommend the following book: Ghost Rails III Electrics. by Wayne A. Cole, Colebooks (2007).

To give just a little background the following are some of the companies that were involved in the broader picture of this topic:

Youngstown and Ohio River Railroad

Upper Ohio Valley Traction

East Liverpool and Wellsville Railway Company

Ohio Valley Scenic Route

East Liverpool Traction and Light

Chester and Rock Springs Railway

Little Beaver Creek Electric Coal Railroad

Smith Ferry Coal, Railroad

Steubenville and East Liverpool Traction and Light

Newell Bridge and Railway Company

Steubenville East Liverpool and Beaver Valley Traction. (Source: Ghost Rails III Electrics By Wayne A. Cole.

East Liverpool annexed its last major addition in February of 1899. At that time the city's corporate borders were extended further to the north and to the east in the general directions of earlier additions. The area annexed northwest of the central city included the land owned by the Pleasant Heights Land and Improvement Company in the general area of Spring Grove and St. Aloysius Cemeteries. Directly north of the city, the extension included the Gardendale section and a strip of territory east of Calcutta Road (St. Clair Avenue) as far north as Riverview Cemetery. To the east, the city annexed the village of Dixonville which had been platted in 1889, land owned by the Puritan Land Company adjacent to the existing eastern boundary of the city, and the areas of the east end known as Helenna, Oakland, and Klondyke along the Ohio River. With the addition of this territory, the city limits now reached to the Pennsylvania border in a narrow strip along the river. By November of 1903 a total of 141 additions had been made to the city. Real estate speculation in outlying undeveloped areas was rampant. Numerous land companies were formed with the express purpose of platting additions and selling lots to prospective home owners. The general prosperity of the era and the creation of new subdivisions, generally along streetcar lines, accelerated East Liverpool's maturity and growth. By the end of the nineteenth century, East Liverpool encompassed 2,880 acres, or about four and one-half square miles.'

The extension of the city's boundaries and the rapid development of outlying areas was made possible by the construction of the electric streetcar system and land company development activity. Both of these factors occurred simultaneously and were interdependent. The need for a system to transport large numbers of passengers in America's major cities was demonstrated at an early date. The omnibus, pulled on a track by a horse, made its appearance in several Ohio cities during the 1860s. The cable car was introduced in San Francisco in 1873. Streetcar systems really came into their own, however, during the 1880s when the idea of using electricity to power them became popular.'

The first mention of a street railway in the East Liverpool area occurred in 1882 when the formation of a stock company to construct a line between Wellsville and the western end of the "Crockery City" was proposed. Interest in the venture, however, was not forthcoming and the proposal languished. A group of local capitalists led by Jason Brookes, T.F. Anderson, and H.A. McNicol incorporated a street railway company in 1888 to build a line between the east and west ends of the city. City council passed an ordinance in August 1889 granting the East Liverpool Street Railway Company the right to construct, operate, and maintain a system for twenty-five years. The line was to begin on Jethro Street, pass through the central city, and continue to the eastern limits of the city. Whether this organization was under-capitalized or failed to obtain the necessary right of way is not known, but it did not inaugurate a streetcar system in East Liverpool. The following year a new company, consisting of John Thompson, H.R. Hill, Will Harker, and a group of Pittsburgh capitalists, was organized to establish a system in the city. The editor of the Crisis felt that the streetcar system would be of great benefit to the east end where there still was plenty of room for growth. He stated, "The east end ceased to grow when a sufficient number of houses were built to accommodate the limited number of inhabitants that worked at the pipe works or the pottery along the river ....8

Almost immediately a rival company, headed by Augustus Armstrong and Erheart Knaver of New York, appeared and expressed an interest in bidding on the project. In November 1890 city council announced that the system would not be built because of an "... inability to get a right to the east end ...through private property. These problems were overcome and it was finally agreed that 1 percent of the profits were to be paid to the city for granting a franchise. In April 1891 city council passed an ordinance authorizing the construction of the street railway system by the New York Company. In August another group, headed by Albert L. Johnson of Cleveland and Sidney H. Short, a wealthy inventor and owner of the Short Electric Railway Company, came to East Liverpool and submitted a proposal to construct a streetcar system. Johnson was the brother of Tom L. Johnson, the mayor of Cleveland and a leader in the Democratic party in Ohio. This group proposed a system that included a fifteen-minute schedule within the city limits of East Liverpool and Wellsville and trips between the two towns every thirty minutes. The Cleveland group also required that the county commissioners bear half of the expenses for grading hills and filling hollows on the road between the two cities. Armstrong and the New York group, asserting that they were being "squeezed" out by the Cleveland-based company, combined with local capitalists to combat Johnson and Short. They formed a new corporation whose officers included David Boyce, Isaac Knowles, Henry Goodwin, George P. Ikirt, and several additional pottery manufacturers. This new group predicted that the Cleveland concern would never obtain the right-of- way to the east end or convince the county commissioners to shoulder the expense of building one-half of the road bed.'

The local newspapers were relatively silent on the issue during the next month as politicians and businessmen maneuvered for position. Although it is not known what took place behind the scenes, it was not uncommon in other localities for a great deal of political manipulation and corruption, involving kickbacks and other influence-buying activities, to take place. In any case, the Cleveland group submitted a petition the first week of September stating that they had secured the right-of-way and were ready to begin construction. On 4 September 1891, city council enacted ordinances repealing the legislation granting the franchise to Armstrong and Knaver and authorizing the Johnson company to build and operate a streetcar line. The reason the Cleveland-based company was successful and the group consisting of the city's most prominent and influential leaders failed was never made public."

News that the issue was finally settled after three years of debate, politicking, and controversy was greeted with joy and anticipation. Once the project was assured, the editor of the Review declared, "Hurrah for the Street Railway." Within days after the announcement, a demand for lots in the east end developed and property owners enjoyed a booming business despite substantial increases in property prices. Construction of the streetcar line progressed rapidly. In early December several parties proposed that when East Liverpool and Wellsville were united by the transit system, the two cities should consider consolidating under one municipal government, forming a city of nearly thirty thousand people. The editor of the Review thought this plan would be advisable; however, the urban rivalries and local politics of the day made the idea unrealistic. The official opening of the East Liverpool and Wellsville Electric Railway on 17 December 1891 was celebrated with a grand ceremony. The streetcars, of course, were an instant success. The Review reported that on 4 July 1903 over eleven thousand five-cent fares were paid and an additional four thousand children, who rode free of charge, were also passengers." The anticipated real estate boom in outlying areas, however, did not occur during the first half of the decade because of uncertain tariff legislation, economic problems on a national level, and the 1894 pottery strike.

Following the uncertainty at mid-decade, the construction of new streetcar lines and the development of new sections of the city and its surrounding area proceeded at a remarkable pace. The construction of a bridge spanning the Ohio River between Ohio and West Virginia at East Liverpool was contemplated as early as 1889. The project was revived in 1893 by J.E. McDonald, an East Liverpool attorney who purchased the Marks farm across the Ohio River in West Virginia. In April of 1893 McDonald announced that the East Liverpool Bridge Company, chartered in the State of West Virginia, had been organized to construct the bridge and that twenty thousand dollars in stock subscriptions had already been secured in Hancock County, West Virginia. He hired engineers to survey the area for the best location of the bridge and began to solicit subscriptions in East Liverpool for the balance of the stock. The editor of the Crisis was excited about the prospect of the bridge, citing the deficiencies of depending on ferry service and describing the benefits to the city and the area across the river. The project was temporarily abandoned because of the Panic of 1893. Three years later, in January 1896, the plan was revived and construction began. By this time the city council had authorized the company to locate the entrance to the bridge on city property and it had been secured by the company, which consisted of McDonald, W.L. Smith, A.R. Mackall, other local capitalists, and J.G. Kerny of Montreal."

McDonald and his associates also formed the Chester Land Company to develop the 475 acres of land they owned. This land included Rock Springs Park, which they planned to enlarge and develop as a resort. Additionally, the investors intended to connect the "Crockery City" with their new town by a street railway across the bridge.

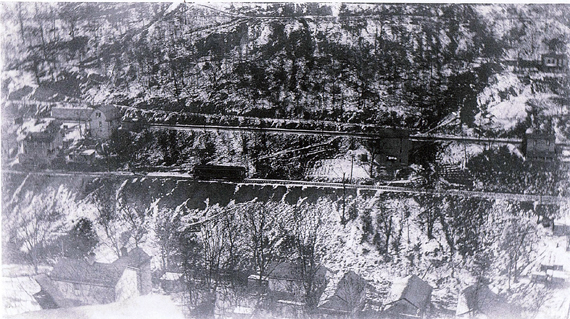

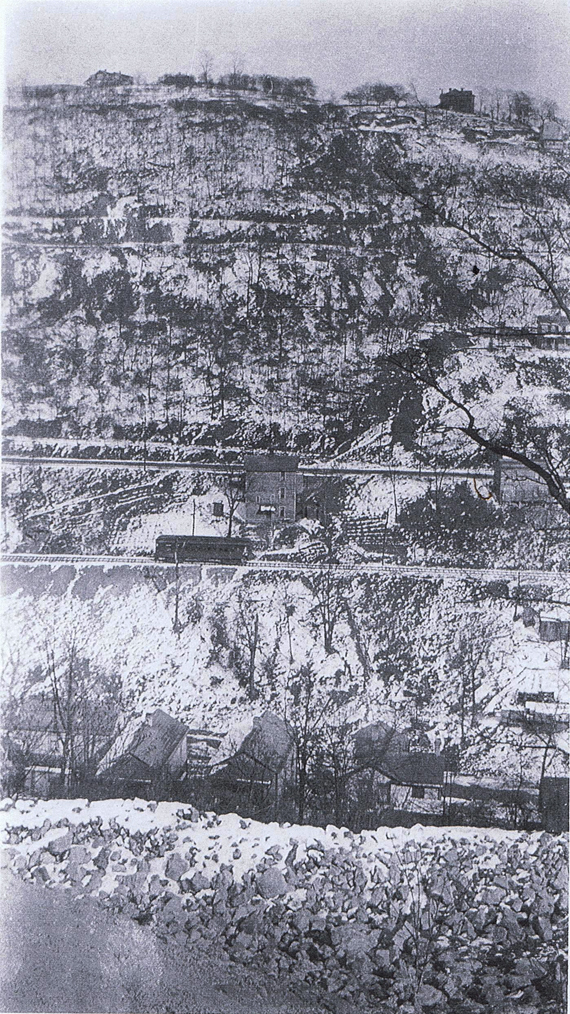

Looking from the Chester side towards East Liverpool. Picture taken of a picture found in the Travelers Hotel.

During the spring of 1896 the promoters surveyed the land and began to plat it into lots. In early July they began to advertise the advantages of the lots 'in [the] new South side suburb at the West Virginia end of the bridge" that would be for sale as of 20 July. Advertisements stated that the new town would enjoy every modern improvement which East Liverpool had and that residents could get gas, telephone, electric, water, and connection with the street railway without paying East Liverpool taxes. McDonald stated that the new area offered plenty of space for the expansion of the rapidly growing pottery industry. The land company placed six hundred lots on sale and the response was good. They reserved about two hundred acres at the eastern end of the property which they planned to donate to prospective manufacturing enterprises. In 1899 the town of Chester, West Virginia was granted a charter. 13

The Chester Bridge, as it was named, was completed and opened to the public on 31 December 1896. Costing over $200,000 to construct, the combination suspension and truss bridge provided a link to a large area of level land. After a little more than a year, the bridge company went into receivership when it could not pay the interest due on its bonds. The bridge was operated by the receivers for about three years. C.A. Smith eventually gained controlling interest in the company and the bridge was later sold to the East Liverpool Traction and Light Company.'4

In the meantime McDonald and his associates began making arrangements for a streetcar line to traverse the new bridge and make their new town more accessible. A dispute over the new line developed between McDonald and East Liverpool officials. Under the terms of McDonald's original proposal, the new line to the Pennsylvania state boundary. Alex G. Chaffin platted a new suburb west of Pennsylvania Avenue and built several houses in 1900. The Supplee Land Company was formed in March 1901 and purchased a tract containing about twenty-one acres which it platted into residential lots. The Island Avenue Land Company platted 169 lots east of Sebring's Klondyke pottery in May 1902 and sold them for prices ranging from fifty dollars to $250. In November 1902 the Midway Land Company began developing a residential area between the central city and the east end along Pennsylvania Avenue. The Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company announced in January 1902 that it planned to build a depot and freight station in the east end at a point opposite the National pottery. Pottery manufacturers and residents alike hailed the news. The editor of the Crisis, citing the number of new merchants and residents, stated in the fall of 1902 that the east end was enjoying an era of business prosperity. The only thing holding the suburb back, he added, was the lack of houses, although they were rapidly being built.'8. THe City of Hills and Kilns, pp 184-190.

Chester and Rock Springs Railway Company

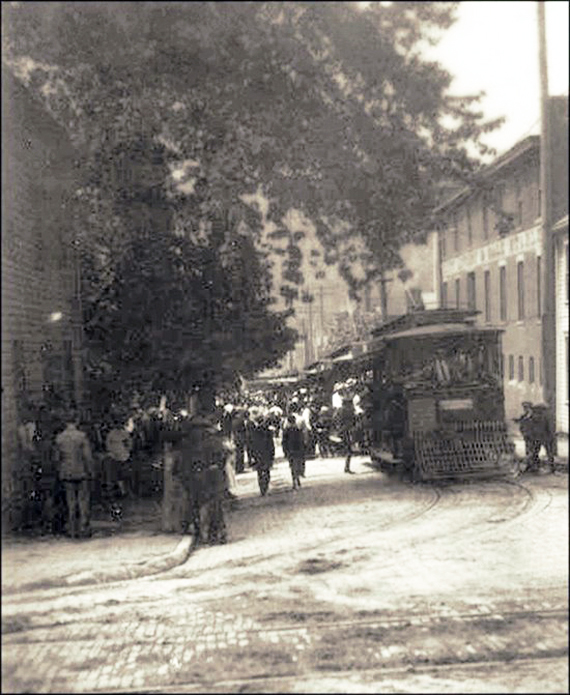

Trolleys lined up on Union Street between East Second Street and East Third Street either taking on passengers for a day at Rocks Springs Park or discharging passengers after a day at Rock Springs Park.

The time period is probably late 1890s or early 1900s.

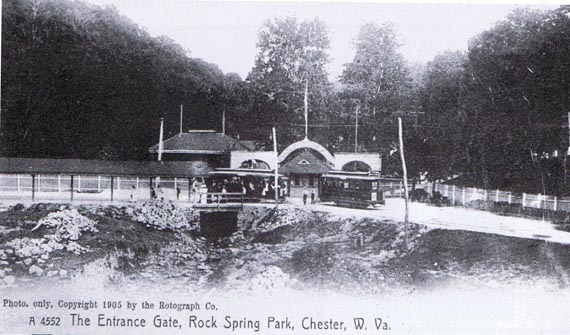

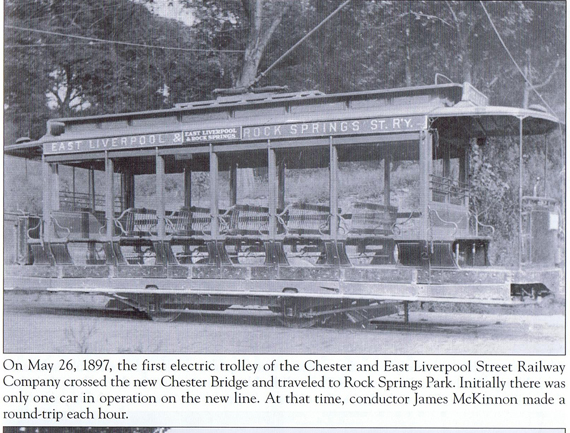

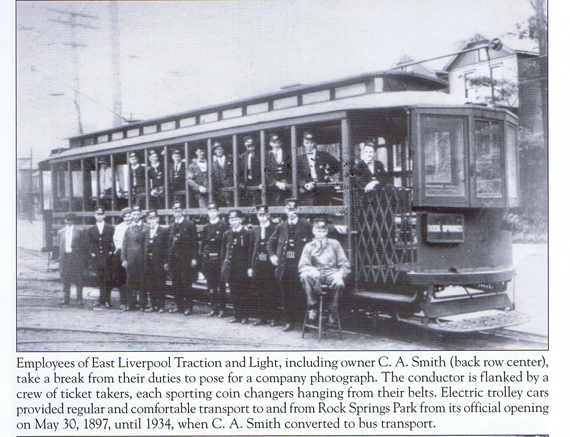

The Chester and Rock Springs Railway Company/East Liverpool and Rock Springs Railway operated from 1897 to 1905. It was absorbed by the East Liverpool Traction and Light in 1905. (Ghost Rails III Electrics by Wayne A. Cole. 2007 p. 164.

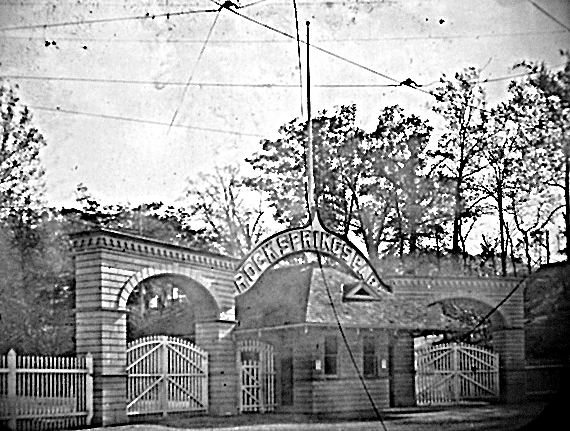

Entrance to Rock Springs Park. Notice the trolley wires.

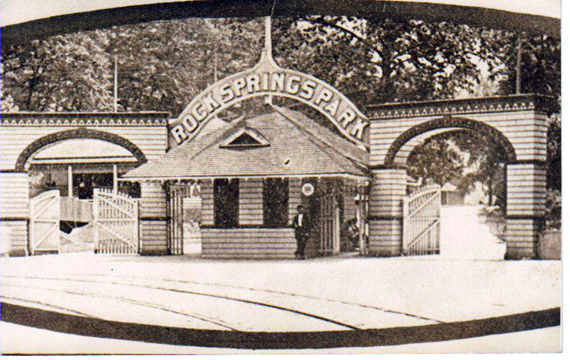

A slightly different angle, you can see trolley tracks.

Employees of the East Liverpool & Rock Springs Park Street Car Company in 1911. Sunday Nov. 12, 1911, 4:30.

Youngstown and Ohio River Railroad

Just a brief overview. This Railroad existed from approximately 1905 to 1931. It has it's roots in a act of the Ohio Legislature of 1832. One that proposed a railroad from Lake Erie to the Ohio River. Over the years there were a number of "paper" railroads, ones that were written up but never became a physical reality, or small portions of a railroads that fit in what could be considered portions of that big lake Erie to Ohio River dream.

Our interest here is that portion of a railroad that actually did exist from Salem to East Liverpool. To be exact that portion of that line from the East Liverpool Road to California Hollow (Carpenter's Run) the West 9th Street area to Dresden Ave to the Diamond.

March 1907, a Y&O along California hollow headed towards East Liverpool.

The California Pottery after it shut down in 1920. It shows the Y&O Line running towards East Liverpool behind what had been the pottery.(ELHS)

Arthur Hall and his wife, the former May Brookes, waiting on a Y&O car arrival. Brookes Family pictures.

A trolley car making its way down California Hollow. Picture courtesy of Timothy Brookes.

A trolley car making its way down California Hollow. Picture courtesy of Timothy Brookes.

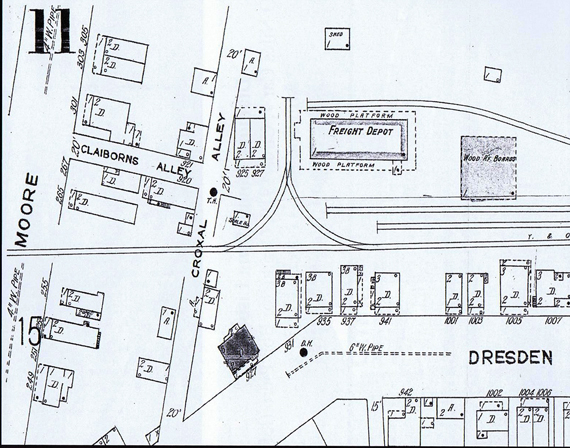

Sanford Fire Insurance Map showing the location of the East Liverpool Y&O Freight House.

East Liverpool Y&O Freight House.(ELHS)

From West 9th Street the Y&O, by agreement, used the East Liverpool Train & Light tracks up Dresden Ave into the diamond. (Ghost Rails III Electrics, by Wayne A. Cole).

A Y&O Car in front of the Little Building sometime after 1915. (ELHS)

The Trolley Transportation Days 2

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law

though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.