| Burr McIntosh, A biography by the late Glenn H. Waight, former editor of The Evening Review. |

Burr McIntosh

So Much Talent,

So Much Energy,

So Much Cheer

By Glenn H. Waight

He was swimming valiantly toward the Cuban shore, determined to file reports and photograph American troops landing to do battle with the Spaniards in Mr. Hearst's wonderful war of 1898.

Burr McIntosh -- actor, newsman, author, lecturer, athlete, poet and pleasant chap -had not left Ohio or Princeton or the New York stage to work for Leslie's Weekly just to watch the historic event from the deck of a ship.

Although banned by the Army along with the rest of the press from leaving the transport vessel to join the invasion, Burr had handed his camera and equipment to a friendly officer for safekeeping. After the landing crafts had departed, he slipped off his outer garments and jumped into the salty waters off Santiago.

Before long he was picked up by an Army boat heading for shore. The boat commander asked, "What are you doing?" The actor/journalist answered innocently, "I fell overboard."

McIntosh went on to take pictures of the first U.S. artillery shots fired at San Juan Hill June 30, 1898, and briefly covered other action in Cuba before he was felled by the tropical fever which claimed many lives in the liberation of the island.

He returned to recuperate and write one of his seven books, "The Little I Saw of Cuba" -- containing many of his photos -- and to go back to the New York and London stages. He later published the Burr McIntosh illustrated Monthly, among the early if not the first magazine devoted to photographic news coverage.

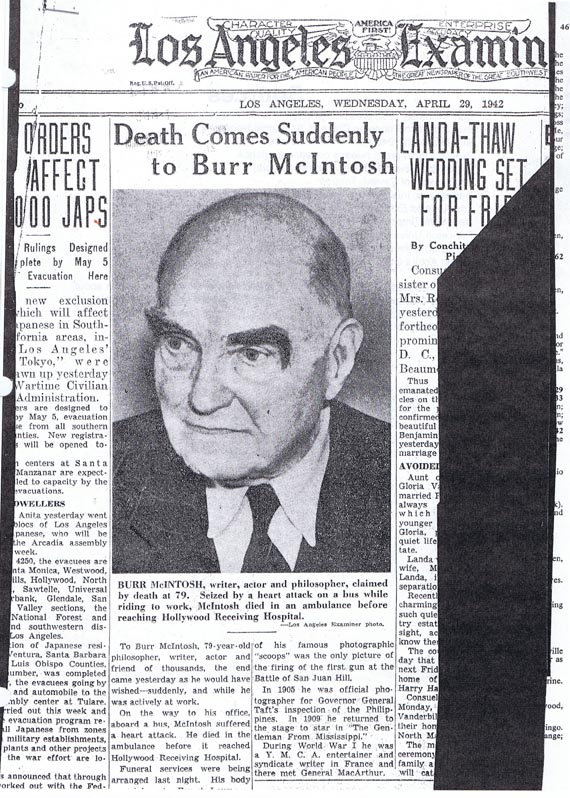

McINTOSH HAD WHAT was described as an optimistic, out-going personality, and in press circles was referred to as the "cheerful correspondent." He met many of the famed men and women of his day, and was familiar with leaders in the literary and art world. Turn of the century photographs show him as a tall, heavy man with a mustache in a rounded face and thinning hair parted in the middle.

He attended three universities, including Princeton where he was a star athlete. His pictorial magazine was produced by the Burr McIntosh Publishing Co. of New York between 1903 and 1910. He served as editor from April 1903 until March 1905, followed by Hobart until publication ended.

McIntosh later moved to California and entered the movies, earning lead roles such as in "On the Banks of the Wabash" produced in 1924. He appeared in more than 25 films.

Burr William McIntosh was a nephew of Homer and Cornelia Bottenberg Laughlin of East Liverpool, Ohio. Laughlin had founded the famous pottery of his name which still produces Fiesta ware and other ceramic products at nearby Newell, W. Va.

In 1884 McIntosh was a captain with the "Hampton Guards," a Pittsburgh marching group of men over six feet tail. They took part that year in an East Liverpool Republican parade supporting James Elaine for President. The men were served lunch in front of the ornate Laughlin home on Broadway.

Burr was born in Wellsville Aug. 21, 1862, a son of William A. and Minerva Bottenberg and grandson of John S. Macintosh and Levi Bottenberg of Wellsville. John McIntosh owned a Main St. drygoods store -- McIntosh and Smith -and with John McCullough operated one of the first banks in Wellsville in what was the McIntosh House at Fourth and Riverside.

Burrs father, William, was a trustee of Wellsville in 1860-61. He and Minerva Bottenberg were married Dec. 28, 1859, and had two other children -- John Stone McIntosh, born Dec. 22. 1860, and Nancy Isabel.

John, an invalid from a spinal injury in an accident, died in 1889. Nancy became an operetta singer.

Levi Bottenberg and P. F. Geisse in 1836 had formed the Fulton Iron Co. which produced castings and machinery. This later became the Stevenson Co.

Sources report the family moved to Cleveland then to Sewickley, Pa.. His father became president of the New York and Cleveland Gas Coal Co. at Pittsburgh, a post he held for 17 years.

Burr attended the Western University of Pennsylvania (now Pitt) in 1879, and in 1880 entered Lafayette College where he distinguished himself in athletics, especially baseball, playing catcher on one of the college's greatest teams. The pitcher was Peyton C. March who became a top general in the American Expeditionary Force in France during World War One. He and Gen. March were the two Lafayette class survivors honored at the 50th anniversary in 1934.

He went on to Princeton in the fall of 1882, and played football, and in the spring set records in the 100-yard dash and 120-yard hurdles. He later listed chemistry as his field of interest, probably the foundation of his photo career.

Burr left Princeton in 1883 (the university records him as a non-graduating member of the Class of '84) and apparently worked for his father in the coal business for a time while organizing many athletic clubs.

BUT JOURNALISM called, and in December 1884, he was hired as a reporter for the Philadelphia News. After about a year, he received an acting offer, and went to New York to make his professional stage debut in Bartley Campbell's "Paquita" Aug. 31, 1885, at the 14th Street Theater.

McIntosh was part of the stage company of Kate Claxton which presented a play at the East Liverpool Opera House in January 1886. He toured with Claxton, and in 1888 joined Augustin Daly's stage company in London.

During a slack period, he returned to newspaper work then went back to New York to appear in "Midnight Bell" whose cast included Maude Adams (1872-1953). In 1889 he joined Arthur Rehan's company which went to England in 1890, opening at Irving's Lyceum theater.

He later played in London under the management of George Ashton who was "purveyor' to Queen Victoria and later King Edward VII. Returning to New York, McIntosh played the lead role in the London hit, "New Lamps for Old." The next year he earned acclaim with the character Col. Calhoun Brooker in the play "John Needham's Double."

Other lead roles followed -- Col. John Moberly in "Alabama" and Jo Vernon in "Mizzouri."

In 1895 he opened at Boston's Park Theater in the famous production of "Trilby" which featured such notables as Virginia Harned and Willard Lackaye. His depiction of the character Taffy reportedly stamped him as an outstanding actor.

Then came one of his major successes when in 1898 he joined part of the original cast of "Way Down East" as Squire Bartlett. A conventional but popular pastoral drama by Lottie Blair Parker, it opened in February at the Manhattan theater in New York. McIntosh, then 36, probably filled the role of the stem father of a man who falls in love with a bedraggled woman who came to the home for help after leaving her child in a graveyard.

But the Spanish-American War broke out, and the newsman/photographer left the play to work for Leslie's Weekly. "I was too old to enter the Army," he later wrote. Burr not only served Leslie's but represented the Hearst papers "and others."

He went to Florida to join the troops, and traveled on ship to Cuba where he took part in the landings and followed them to Siboney and San Juan Hill. He later said his photos of the landings of Gen. Shafter's forces at Daiquiri June 22 and the Rough Riders battlefield of June 24 were published in the New York Evening Journal four days before any others from the front.

"A week later, July 1," he recalled, "I took the only photographs of the first shot from the first gun fired from El Poso Hill, and 24 minutes later the effect of the first shrapnel from San Juan Hill after it passed over our heads on El Poso Hill and burst amongst the Rough Riders and others. Thirteen of the former were killed, and more than 30 wounded by it."

Apart from being fired upon by Spanish artillery, he saw little combat action before falling prey to yellow fever. He spent days in several Army field hospitals, becoming very ill and losing 71 pounds. He eventually returned to the United States and was hospitalized for some time.

In his book, "The Little I Saw of Cuba," he was critical of Gen. Shafter and Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt of the Rough Riders for their military decisions and Roosevelt's apparent inflation of his own role in the fighting.

Mcintosh's literary style in the book, albeit drily humorous at times, was stilted and of limited journalistic value. Much was written about his Princeton friends in Cuba and the circle of journalists covering the war. As a photographer, he admitted many of his pictures "did not develop," and too many were taken at a distance from subjects facing away from the camera during meetings or surveying the hills.

DESPITE THE LINGERING effects of the fever, in 1899 he accompanied Nat Goodwin and Maxine Elliott to London to appear in "The Cowboy and the Lady."

Back to New York he launched a new venture, opening in 1901 a photographic studio on 33rd St. where many stage figures came for portraits, including Ethel Barrymore, Maude Adams, Julia Marlowe, Lily Langtry and Edna May.

Next, it was back to the boards in 1900 when he went on tour with Mary Mannerling in "Janice Meredith." His illustrated monthly was launched in 1903, its notable photos and new approach to news drew considerable attention. This probably resulted in his being named "official photographer" for Secretary of War William Howard Taft's 1905 inspection tour of the Philippines and Orient, bringing back some 2,000 negatives.

On his return, he undertook an illustrated lecture tour based on the trip, "Our Country and its Future." This venture enhanced the image of Taft who became President in 1908.

The footlights lured him again, and in 1910-11 he toured the U.S. in "The Gentleman from Mississippi." Then he fell down an elevator shaft, twisting his spine and fracturing an ankle. But true to his motto, he "kept a-going."

McIntosh went to California in 1913 to enter the movies, appearing in his first silent film, "Get Rich Quick Wallingford." His versatility brought other roles, including many he had played on the stage. He earned the lead in "On the Banks of the Wabash" produced in 1924. The Twenties also found him in his old stage role in "Way Down East."

On Dec. 23, 1914, he had married Mrs. Jean Snowden Luther. They were divorced in 1929.

When the U.S. entered World War One in 1917, he volunteered for Liberty Bond drives, and sold more than five million dollars worth. Then he served the Red Cross fund effort, obtaining more than a half million dollars. Offering himself to the YMCA, he was sent to France and Germany as a lecturer/entertainer, enjoying popularity with the servicemen until hospitalized at Coblenz, Germany, with arthritis.

McIntosh debuted on radio in 1922 as the "Cheerful Philosopher," broadcasting twice a week on WEAF in New York for seven months, then in 1923 once a week on WJZ for six months. But arthritis struck again, and he suffered for a whole year.

Returning to Hollywood, he organized a motion picture company, hoping to use its profits to finance a cherished dream -- establishing a center of culture and the arts. He told friends he wanted to buy a 1,500-acre tract with 50 acres each set aside for the fine arts, literature, music, drama, etc.

However, he was unable to achieve his dream, and settled down to life as the "Cheerful Philosopher" inspiring the sad and the ailing. His books, "Cheerful Philosophy Poems," Volumes I and II, reportedly achieved wide distribution.

On his 63rd birthday anniversary in 1925, he was honored at New York with a reception at which he gave a review at a Broadway theater. Proceeds went to an American Legion endowment fund.

He compared his life to a mile-long track, with flags at the quarter mile marks, each representing 21 miles. The first represented childhood, the second, youth, and the third, middle age, he said, describing himself as now "going down the stretch."

"When I reach 84 and the floral wreath has been put away in mothballs, I'm going out into green pastures and browse around and take it easy," he declared. "But not until then."

AN ARTICLE in the East Liverpool Review-Tribune, reporting this event, listed McIntosh's plans for the immediate future. They included motion picture work, continuing the "Cheerio" and "Keep a-Goin" radio talks he had resumed in Hollywood, and writing a daily 500-word column about his personal reminiscences to be published by a national syndicate.

Since moving to Los Angeles he had been broadcasting on station KHJ for five months, KMTR for a year and on KFWB with his Sunday morning program.

In 1929 he was one of the leads in the talking picture, "Fancy Baggage." (A Review April 15, 1929, article referred to his "gruff manner of speech.")

In observance of his 70th birthday anniversary in 1932 a group of friends arranged a special celebration. One of those present, John McGroarty, described the scene:

Folks crowded in on Burr, folks who love him as all the world loves him. And as he stood there among his friends, gray and a little bald, you would never think that once he was champion foot racer, a dare-devil war correspondent, a movie actor, lecturer and a thousand other things a man can be in seventy years besides being the first man in America to teach photographers really how to take pictures.

He is just not an old man yet. But he has mellowed a lot. He is quiet now, and takes fife as only a true philosopher knows how to take it easy. He has builded up about him a tremendous love out of the hearts of his fellow man. 'Love begets love.'

One of his projects had become the Los Angeles Breakfast Club, presiding as "The Apostle of Friendship over the Wednesday morning event attended by notables. A photo in the Los Angeles Examiner showed him giving the membership oath to actress

May Robson and other distinguished celebrities. McIntosh would close the broadcast with a poem, story. or comments.

He had become in great demand as a speaker, known for his theme of fellowship, love and encouragement, to "keep a-goin'." He showed a desire to help the distressed to be courageous and positive. He appeared before service clubs, patriotic groups, students at schools and colleges and other organizations.

In an update of his Princeton Class of '84 file, he said he was 'interested in the welfare of service men and women, the blind, the hard of hearing and unfortunates in general.'

One of the tales told of his commitment concerned an invitation to attend a Hollywood meeting of producers picking the cast for a film for which he was being considered. He declined, explaining he had a very important engagement he could not break. He kept the appointment -- giving a Christmas greeting of cheer to residents of the County Poor House.

McIntosh became an honorary member of the Roosevelt Camp and 'Rough Riders" Spanish-American War Veterans, the World War One 42nd "Rainbow Division, the Second Division and the 26th Division Veterans, a member of the advisory board of the Braille Institute of America, Cheery Chase Club for the Blind, and the Beverly Hills Club for the Hard of Hearing.

He belonged to the Southern California alumni units of Princeton, Pitt and Lafayette and Sigma Chi fraternity (59 years), San Fernando Lions Club, and was the 'Ace of Diamonds' at a breakfast bridge club.

His residence was a 6671 Sunset Blvd., Hollywood, and in the 1934 Princeton fiftieth anniversary booklet he invited everyone to his front lawn at the "Crossroads of the World" on his birthday anniversary Saturday Aug. 21, at 11 am. "and from then on through an evening with a full moon overhead -- in memory of having reached the 75th milepost."

He closed with "being imbued with the Spirit of '76" and "Life is Just Beginning."

BURR McINTOSH failed to achieve his hope to start "down the stretch" at 84 and take it easy.

In mid-April 1942 he suffered a mild heart attack. On April 27 he told a friend of a premonition of a "great catastrophe." Despite his failing health, he insisted that night on fulfilling a lecture engagement in which he described his early friendship with Gen. Douglas MacArthur. After this appearance, he said to a business acquaintance, Rogers Adams, "I've just made the best speech of my life."

The next morning, April 28, on a bus en route to his Hollywood office he was stricken with a major coronary seizure. Placed in an ambulance, he died before reaching Hollywood Receiving Hospital. He was 79.

Eighteen distinguished men were pallbearers for the funeral in a church that was packed. A special service was conducted by Sigma Chi fraternity, and at the grave, the United Spanish-American War Veterans sounded taps.

A lengthy obituary in the Princeton alumni bulletin read in part:

He was one of the most versatile and talented men in our class. One rarely meets one who could do so many things and do them well.

'Boy Meets Girl'

Among Burr Mcintosh's literary efforts was "Football and Love," a frothy, fictitious mini-romance (58 pages) based on the Yale-Princeton grid game of 1894.

In it Ned, 14, a light-haired Eastern lad, and 011ie, smaller boy from Kentucky, become roommates and great friends at St. Paul's preparatory school. 011ie, 13, joins the school football team as a quarterback, and persuades his larger friend to go out for the team.

A novice at sports, Ned becomes a capable lineman despite challenges and rough treatment by an older bully whom he knocks over. He also is entranced by the photograph of a lovely young woman on 011ie's desk whom the Kentuckian describes as his "best girl."

At 011ie's invitation Ned spends Christmas with his family, meeting the black-tressed, black-eyed subject in the photo. He is captivated, as she is with him, but no betraying words are exchanged, although he takes back with him a locket containing her picture.

Graduating from St. Paul's, 011ie goes to Yale while Ned, following his late fathers will, enrolls at Princeton. Both eventually earn starting positions on their Ivy League teams, and in their first game on opposite sides, Princeton wins. After the contest, Ned by chance encounters 011ie and the girl, and the two converse but still without revealing mutual interest because of the "false pride of youth."

A year passes. The Tigers and Bulfdogs clash again, this time on a mud-soaked field. Princeton fumbles, and Yale goes on to a touchdown -- the only score during the game in which Ned plays valiantly, even after a bruising kick in the head.

Following the final gun, Ned and 011ie shake hands -- the last time as competing friends. 011ie invites him to a family dinner at the Waldorf, and Ned and his beloved later steal off to an alcove where they talk happily. 011ie comes upon them, suggests it is late and time to retire.

After an awkward pause, Ned blurts out to his longtime friend, "Will you let me have her?" Surprised, 011ie smiles, declaring Ned would have to ask the young lady's mother. "You've got my consent, but after all, I'm only her big brother."

The book was illustrated with quaint drawings by B. West Clinedinst. The paperback was published in 1895 by Transatlantic Publishing Co. of 63 Fifth Ave., New York, and London. An inside page suggested "Read Before 'Uncut Leaves."

McIntosh's Film Credits

(As listed by the Screen Actors Guild. Although he entered films in 1913, the SAG does not include the name of the movie.)

1915 -- Adventures of Wallingford; 1920 -- Way Down East; 1923 -- Driven; The Exciters; On the Banks of the Wabash

1924 -- The Average Woman; Lend Me Your Husband; Reckless Wives; The Spitfire; Virtuous Liars; 1925-- Camille of the Barbary Coast; Enemies of Youth; The Pearl of Love; The Green Archer (serial)

1926-- The Buckaroo Kid; Dangerous Friends; Lightning Reporter; The Wilderness Woman 1927 -- The Golden Stallion (serial); A Hero for the Night; Breakfast at Sunrise; Fire and Steel; Framed; Hazardous Valley; Naughty But Nice; Once and Forever; See You In Jail; Silk Stockings; Taxi! Taxi!; The Yankee Clipper; Non-Support (short)

1928 -- Across the Atlantic; The Adorable Cheat; The Grip on the Yukon; Me, Gangster; The Racket; That Certain Thing; Lilac Time; The Four Flusher; Sailor's Wives

1929 -- The Last Warning; Fancy Baggage; Skinner Steps Out; 1930 -- The Rogue Song; 1933 -- The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi; 1934.- The Richest Girl in the World</p>

Sources

Burr McIntosh 1932 press biography

Burr McIntosh Princeton Class of '84 alumni biography

biography Burr McIntosh 1940 alumni questionnaire

Burr McIntosh press release on war experience

Gilbert & Sullivan Archives, Internet (Utopia)

East Liverpool Review-Tribune

E-Blast site, Internet, (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Los Angeles Examiner</p>

New York Times

Princeton University Archives

Princeton University October Alumni Bulletin Sceen

Actors Guild

I am indebted to James Woodrow of Wellsville for valuable information about the early McIntosh family; to Burchfield Cartright of East Liverpool for gaining access to his Alma Mater, Princeton University, and to Darlene Nossaman of Waco, Tex., for additional family material.

Nancy McIntosh

Burrs sister, Nancy Isabel, also succeed on the stage, earning turn of the century reputation as an operetta singer in England and America, and becoming a close friend of William S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sulivan comic opera fame.

Seeking a concert career, Nancy and her father had gone to England around 1892 both to advance her singing and to forget a tragic event in America.

The father, president of the gas and oil firm, was a member of a Pennsylvania hunting and fishing club whose dam had burst in 1889, allowing a wall of water to obliterate Johnstown with a loss of 2,200 lives.

Nancy was described as "an American without a 'twang,' young, delicately blonde, naive and charming," who had been in London three years. She had sung at the Sunday and Monday popular concerts and those of the London Symphony, and The Times termed her voice as "of great beauty and considerable power."

Gilbert first heard her at a party, and needing a soprano for the part of Princess Zara in his new operetta "Utopia Limited," he asked his partner Arthur Sullivan to hear her. He approved her, and with further training and Gilberts coaching, she drew applause although critics were not greatly impressed.

She was nervous in the first performance of "Utopia Limited," both as singer and actress, and her only solo, "Youth is a boon," was cut after the first night. Sullivan thought she would never be a singer, and told Gilbert, saying she had no 'sympathy' in her voice. But he changed his mind, and urged her to return to the stage, and she continued at the Savoy.

With moderate success and Gilbert's help, she was signed for the lead in the next work, "His Excellency."

ACCORDING TO Gilbert biographer Jane Stedman, Nancy began to see more of the Gilberts, his wife, Lucy, whom he called Kitty, liked her and he found her intelligent and receptive to coaching.

She already had clear enunciation, which he improved, while the fact that she was a good horsewoman endeared her to both. In return, she may have started a youthful crush on Gilbert, she was, after all, the youngest prima donna the Savoy (production company) ever had.

Nancy soon went to live with the Gilberts, becoming almost an adopted daughter. She had a good voice, and Gilbert trained her as an actress so that she became equal to the demands put upon her. His enthusiasm for those whose ability he liked aroused antagonism in some who were asked to share his admiration, and this happened with Nancy at times.

She was troubled by a series of bad throats, missed performances and money. People were kind, gifts came from Gilbert, Kitty Gilbert and Sullivan and others. Then Gilbert got her the part of Dorothy in "Dan'l Druce" which he was directed, she was weak in the first performance, but redeemed herself in the second.

Nevertheless, Sullivan and D'Oyly Carte were dissatisfied, wanted to get rid of her. Helen Carte wonder why "such a really amiable and sweet girl. . . should be such a wet blanket and such a damper on the performance."

The notable Gilbert and Sullivan split again over this. Kitty liked Nancy, and her stubborn husband turned to composer George Henschel. She appeared in "His Excellency" in a minor role.

Nancy did not spend Christmas 1897 at Gilberts. She had secured an engagement in America, playing in "The Circus." She appeared in "The Geisha," and the Boston Gazette termed her "simply perfect." Despite rumors she would appear in a play with brother Burr, she did nothing further.

Returning to Britain, Nancy accompanied the Gilberts on most of their journeys abroad, twice to Wiesbaden, to the Crimea and Caucus, Lake of Geneva, Flume, Venice, Paris, Azores, Portugal, Constantinople.

She did not return to the stage until 1909, singing at church and for friends, giving lessons, taking over more duties as the daughter of the house, although never legally adopted.

In 1909 Gilbert put Nancy in role of Faery Queen in "Fallen Fairies." She was now in her early 40s, and had not acted for more than 10 years. It opened in December, winning audience enthusiasm but critics were not unanimous.

Nancy and the cast received praise for enunciation, and her singing was described as fresh, her silvery speaking voice reminiscent of Ellen Terry. But several critics cited her lack of sonority or vocal strength. Sixteen years previous the press perceived her as an ice maiden, a girl made of moonlight, not as the fairy queen driven to fury by faithless human love.

Many believed she failed to project sexuality. A female chorus member years later said she lacked 'star' quality, a spinster who would never attract a man.

The producer, Herbert Workman, notified Gilbert he would remove Nancy, and had replacements ready. He said Nancy's singing was so out of tune that groups would leave the theater or not come at all. Not for three days did Gilbert tell Nancy, but she took the news "avec beaucoup de courage."

The angry Gilbert obtained injunction to prevent her song from being sung. The producer met Gilbert's conditions of apology and explanation, but production closed, and Gilbert and Nancy sued for breach of contract and fees. They finally withdrew the suit for payment of costs. Nancy went to Vienna 'under contract,' Gilbert not explaining with whom.

SOME LOCAL PEOPLE hinted she was his mistress. This seemed doubtful, according to Stedman, for in the late 1890s Gilbert had a hernia, making intercourse painful, plus he suffered the onset of diabetes which would make it infrequent. Nor was he the kind of man who would bring home a mistress to live with his wife. She was also Kitty's comp-anion and friend of the family.

After Gilbert died, Nancy lived with his widow 25 years, like a daughter deferring to an aged mother. No doubt Nancy loved 'The Judge, 'as she called him, but not with consciously sexual love.

Brother Burr was among the many notables who sent condolences at Gilbert's death. Gilbert was cremated, and his ashes placed in an oak casket buried at Stanmore where where Nancy had lined the grave with white flowers. She and widow Lucy took bouquets to his burial plot every Sunday for some time, then on his birth date and date of death, finally the elderly Nancy visited the grave every three months.

Gilbert left 118,000 pounds, double that of Sullivan's estate. He assigned all of it to Lucy (whom he called 'Kitty' from an early endearment 'Kittens'), including the Garrick Theater which after her death would go to Nancy, and after that to the Actors Benevolent Fund.

Nancy died sometime in 1954 at the age of 80.

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.