| This article originally appeared in the 18th Annual Tri-State Pottery Festival 1985 Plate Turner's Handbook. June 13, 14, 15, 1985. |

THE CALIFORNIA POTTERY

(1868 - 1898)

by Timothy R. Brookes

While some of this city's early potteries were fortunate enough, or well-organized enough, to become giants in the industry and gain nationwide recognition, the majority failed to achieve that sort of success. Even so, these lesser concerns were an essential part of industrial life in 19th Century East Liverpool and their stories are an integral part of the area's history.

A prime example of these little known operations was a small concern which had a life-span of nearly thirty years, but failed to achieve lasting success and is now largely forgotten.

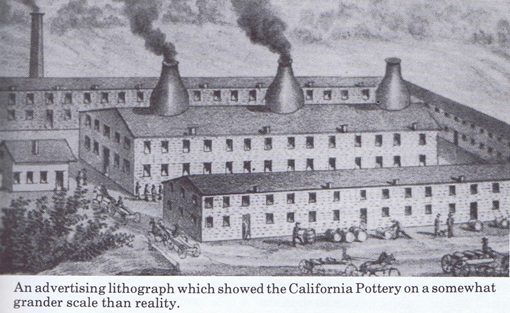

The California Pottery was, as its name implies, situated in the valley through which both Dresden Avenue and Route 11 pass and which is still referred to by some as California Hollow. According to early newspaper accounts, the firm was first organized as a stock company in 1868 by Edward McDevitt, Ferdinand Keffer, Joseph Moreton and David Hallum, and was known as McDevitt, Keffer and Co.

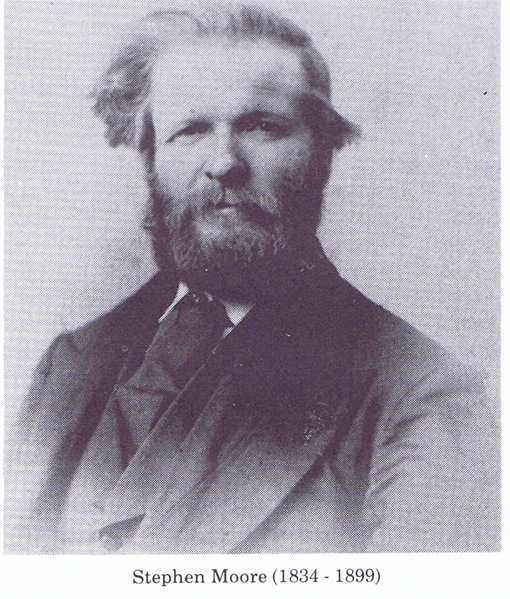

During the first few years of operation, the name of the firm changed repeatedly as disputes and difficulties between the partners led to constant personnel changes. A permanent change occurred in 1869 when Stephen Moore, an English potter, purchased an interest.

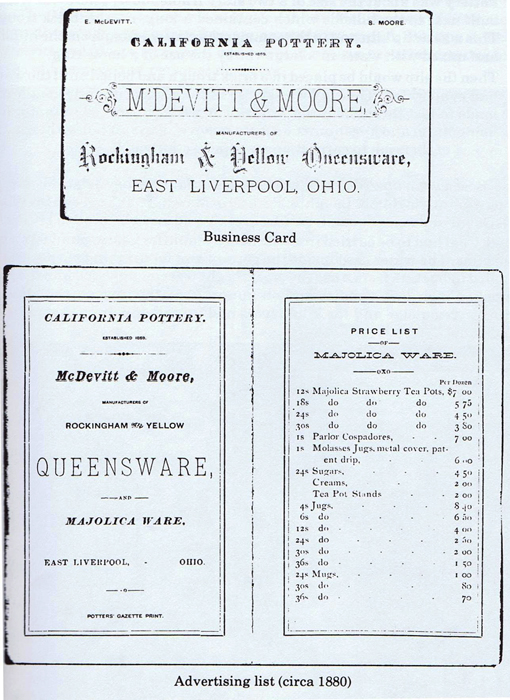

The constant change in the partners comprising the California Pottery ended in 1874 when Pierce Curby withdrew leaving Edward McDevitt and Stephen Moore as the sole proprietors. The tenure of these two gentlemen would last nearly twenty years and the firm would achieve its greatest recognition under the name "McDevitt and Moore".

A native of Donegal, Ireland, Edward McDevitt was born in 1831 and was one of nine children. At age 12, he went to Glasgow to serve a 6 year apprenticeship in a pottery. He emigrated to the U.S. in 1854 and stayed in the vicinity of Boston for five years. In 1859, McDevitt came to East Liverpool and worked at the S and W Baggott pottery for five years and later spent several years with other firms.

The English half of this Anglo-Irish concern had a similar background. Stephen Moore was born in Burslem (one of the "Five-towns" comprising Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire) in 1834. Like most families in that famed pottery-producing area, the Moore children began to work in potteries at an early age. The 1851 English census listed Stephen as a 16 year old slip- maker. His younger brothers and sisters were also engaged in pottery work. This may have been due to financial necessity as their father, Stephen Moore, Sr., had died at age 45 of potter's asthma.

In 1858, the younger Stephen Moore, having completed his apprenticeship, left his home in Staffordshire and traveled to East Liverpool where he immediately found work and sent back for his wife and son. During the Civil War, Moore served for one year in a New Jersey regiment, though why he did not enlist in a local unit has never been discovered.

After the disruption of the Civil War years, many new pottery businesses were initiated in East Liverpool and the California Pottery was one of these. Neither McDevitt nor Moore could have ever realistically hoped to operate their own pottery in their native land. In the wide-open American setting, however, anyone with the requisite skill, daring, and a small amount of capital could make the attempt.

In 1876, an article in the East Liverpool Tribune detailed the, then recent, history of McDevitt and Moore, including the many shifts in ownership and commented that the firm, "now seems to be stable". The product of the pottery consisted of Rockingham and yellow-ware and the capacity of the plant was estimated at 700 packages per year. The plant boasted two kilns and approximately twenty employees.

The firm's biggest problem was its location - more than a mile from the C. & P. RR Depot on Second Street. The reason for the out of the way site was the existence of large deposits of coal and clay on the premises, which reduced expenses considerably. Unfortunately, the benefits of having such easy access to raw materials were largely offset by the extreme difficulties encountered in hauling the finished ware to the depot.

The Tribune's reporter noted this drawback but stated that the projected railroad from East Liverpool to Lake Erie would pass within 50 yards of the McDevitt and Moore warehouse. Like many other such plans, this railroad never materialized and during the firm's entire existence, the problem of hauling ware by wagon over the inadequate roads was never solved.

One of the earliest employees at the California Pottery, John Bosen, was interviewed in 1942 at which time he had amassed a total of 63 years service in various East Liverpool potteries. Bosen was only a boy when he worked at the California Pottery as a coal-hauler, water boy, fire tender, and clay wedger. When asked about his first employment, Bosen commented:

"There is as much difference between the modern pottery and the ones I worked in when a boy as between a big barn and a pigsty. The California Pottery was about the size of a two story framehouse. There was a shed built next to the hillside which contained a long, narrow brick trough. This was a slip kiln and in the summer the clay was dug from the hillside and mixed with water in a large vat by the use of a horse ring. Then the slip would be placed in a brick trough and boiled until the water had evaporated. The clay was stored in the basement and enough was made to last throughout the winter. The wedgers worked in that damp hole cutting and kneading the clay to remove all the air holes, then it was a part of their job to carry it up an outside stairway."

Bosen went on to describe working conditions as they existed before he took a job at the Homer Laughlin Pottery in March, 1880. To reach the plant, McDevitt and Moore's employees frequently had to wade through knee-deep mud. Coal had to be carried from the nearby mine for heating and for firing the kilns. The water used inside the pottery and for drinking purposes was hauled in buckets from a nearby creek. Light was not provided and the men supplied their own candles and oil lamps. If all that wasn't enough, the kilns were outside and the kilnplacers had to load and draw them in rain and snow.

Despite these hardships, the pottery was slowly expanding. An 1879 report stated that the firm's three buildings measured 50' x 40', 40' x 15', and 28' x 28'. Production had increased to 1,000 packages annually, even though horsepower was still employed in the grinding shop and in propelling other machinery. The article also indicated that their ware was available nationwide but was marketed chiefly in Baltimore, Boston and Chicago.

The 1880's were a time when McDevitt and Moore received little mention in the local press and the firm appparently prospered. Starting in 1892, McDevitt and Moore received a great deal of newspaper attention due to a series of business and personal disasters.

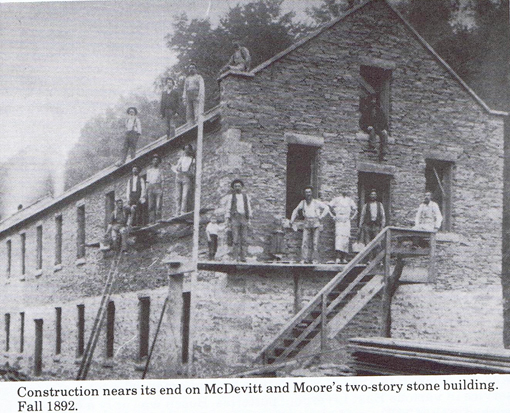

On May 21, 1892, the Tribune reported that a fire occurring the previous Sunday had damaged a large part of the plant with estimates approaching $5,000.00. The company had 50 employees at the time and the owners promised that they would rebuild.

Within a few weeks, temporary sheds had been erected and production was resumed with new machinery, At the same time, it was announced that plans for a new, two-story stone building measuring 25' x 105' had been drawn. In November, the new building was completed and was expected to increase the capacity of the plant three fold.

A second and even more harmful fire struck McDevitt and Moore on the night of November 12, 1893. As reported the next day in The Daily Crisis, nothing could be done for the "isolated factory" which was located beyond the city limits, and thus out of the jurisdiction of the E.L. Fire Department. The fire completely destroyed the frame building which contained the firm's engine room, sliphouse and saggerhouse in less than an hour. The new stone building escaped damage. McDevitt, who lived next door to the pottery discovered the fire about 11:00 p.m. An insurance company had earlier refused to cover the frame buildings, although they did insure the stone structure. The damage was estimated at $12,000.00, which was a staggering loss to a firm the size of McDevitt and Moore.

This second fire was likely the last straw for the partners and on February 3, 1894, a legal notice in the Tribune announced the dissolution of partnership of McDevitt and Moore with McDevitt retiring. The business was to continue under the firm name of Stephen Moore and Co.

Edward McDevitt was elected to a township office in April, 1894, and died on December 24, 1896, at the home of his son, Peter.

Stephen Moore continued as best he could with operations at the plant. In February, 1897 a local paper reported that the California Pottery had begun to manufacture ceramic washboards and had sent a shipment to Harrisburg, Pa. The California Pottery never made the tansition to white- ware, and the demand for Rockingham and yellow-ware had greatly diminished as the public began to demand a more refined product.

On November 1, 1897, a foreclosure suit was filed by the First National Bank against Stephen Moore and Co. The bank had loaned the sum of $2,350.00 to Stephen Moore, his sons, Alfred and John, and his sons-in-law, Frank Leonard and William Pittenger, in January 1894 and had renewed the notes several times.

Thereafter, the local press contained a series of notices concerning the foreclosure, attempts to reorganize and finally the sheriff's sale of the pottery premises in August 1899. Stephen Moore did not long survive the sale of the pottery to which he had devoted most of his adult life. He died September 7, 1899 from the same lung affliction that had caused his father's premature death.

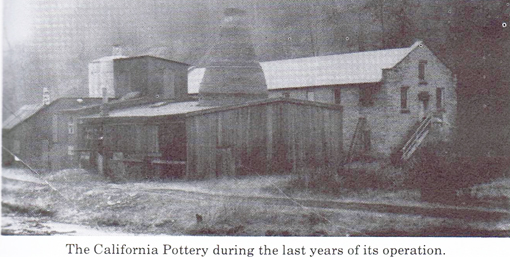

The California Pottery possibly after it ceased operations.

The California Pottery possibly after it ceased operations.

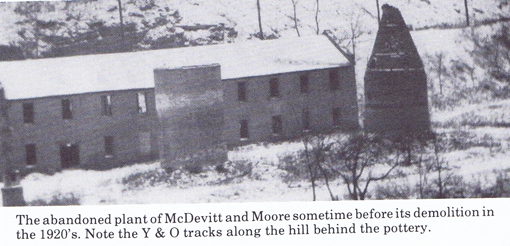

The stone building that had proved its worth against fire and the upright kilns remained standing for many years and were demolished sometime during the 1920's. The site of the California Pottery is now buried beneath Route 11 and the surviving examples of ware from the plant are very rare. Unlike most of East Liverpool's potteries, McDevitt and Moore are not known to have ever used any distinctive markings on their products. As a result, only a handful of pieces owned by the Museum of Ceramics and by descendants of the owners can definitely be attributed to the firm.

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.